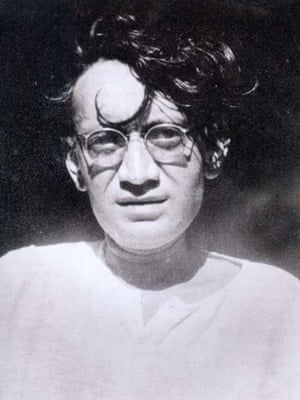

Saadat Hasan Manto

Celebrated for his stories of Indian partition, Saadat Hasan Manto was a distressingly prophetic and daring writer. But would his work have found a publisher today?

It was the greatest mass movement of humanity in history. In the days and months leading up to the partitioning of India in August 1947, 14 million people moved and two million died as the new nation of Pakistan was created. The borderline was arbitrary and artificial – established in haste by a British barrister called Sir Cyril Radcliffe – and in trying to slice India along religious lines, it turned former Muslim, Hindu and Sikh friends and neighbours against each other.

The partition was brutal and bloody, and to Saadat Hasan Manto, a Muslim journalist, short-story author and Indian film screenwriter living in Bombay, it appeared maddeningly senseless. Manto was already an established writer before August 1947, but the stories he would go on to write about partition would come to cement his reputation. Though his working life was cut short by an addiction to alcohol, leading to his death at 43, Manto produced 20 collections of short stories, five collections of radio dramas, three of essays, two of sketches, one novel and a clutch of film scripts. He wrote about sex and desire, alcoholics and prostitutes, and he was charged with obscenity six times. In his journalism, he predicted the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Pakistan. But it is for his stories of partition that he is best remembered: as the greatest chronicler of this most savage episode in the region’s history.

He may be largely unknown in the west, but as the 70th anniversary of partition looms next year, there has been a re-emergence of interest in the life of Manto. A Pakistani biopic was released last September and last month in Cannes it was announced that a new Indian film will be made about the writer who has been compared to DH Lawrence, Oscar Wilde and Guy de Maupassant.

Saadat Hasan Manto was born into a middle-class Muslim family in the predominantly Sikh city of Ludhiana in 1912. In his early 20s he translated Russian, French and English short stories into Urdu, and through studying the work of western writers he learned the art of short story writing. He usually wrote an entire story in one sitting, with very few corrections, and his subjects tended to be those on the fringes of society. The historian Ayesha Jalal, (who is Manto’s grand-niece) wrote in her book about him, The Pity of Partition: “Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps or criminals, Manto wanted to impress upon his readers that these disreputable

people were also human, much more than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy.”

One such story “Bu” (“Smell”) was about a sexual encounter between a prostitute and a rich young man who is intoxicated by the smell of her armpits. It prompted the first of Manto’s run-ins with British law – he was charged with obscenity but not convicted. “Manto’s stories were radical in their own time and they are still radical,” says the author and academic Preti Tanuja. “Manto does not shy away from the idea that women have sexual needs and their own sexual vision that has nothing to do with being in love with someone else.” In “My Name is Radha” a male character is raped by a woman; in “Thanda Gohst” (“Cold meat”) a Sikh man returns home and is stabbed by his wife during sex when he confesses to raping a corpse. “Reading Manto made you realise that literature did not always have to conform,” says the author Mohammed Hanif, whose work shares the black humour and political bite of Manto, “It does not always have to tell polite stories.”

Manto had been implacably opposed to partition and had refused to go to the newly formed Pakistan. One evening he was sitting drinking with his Hindu colleagues at the offices of the newspaper where he worked when one of them remarked that, were it not for the fact they were friends, he would have killed Manto. The next day Manto packed his bags and took his family to Lahore, and it was here that he wrote the stories that revisited the brutality and absurdities of partition. In “Toba Tek Singh”, one of his most famous stories, Hindu and Sikh patients in a Pakistani asylum are moved to India. One of them, a Sikh, is so enraged that he stands on the border between Pakistan and India. Partition, Manto was saying, was madness. “Don’t say that 100,000 Hindus and 100,000 Muslims have been massacred,” he would write, “say that 200,000 human beings have been slaughtered. And it is not such a great tragedy that 200,000 human beings have been butchered but the real tragedy is that the dead have been killed for nothing.” The legacies of partition are still with us – in both the subcontinent and in Britain – and the need to understand it has not diminished with time. “How does this happen? How is it that people who have lived on the same street for centuries turn on each other?” asks Hanif. “How do you kill your best friend? He is one of the few writers who picked on these themes and he wrote ferociously, and he wrote fearlessly.”

|

| Add caption |

I wish I had known about Manto when I was growing up in the UK. The picture of Pakistan I was fed was of a place of conformity and religiosity, where you did not question or mock. It feels both astonishing and inspiring that such a modern writer was alive at the very birth of Pakistan. Manto makes us rethink what we imagine Pakistan to be, and has been treated warily by the state. “He has been celebrated in academia and the arts circle but on a national level there has been if not a shame then a discomfort,” says the actor and film-maker Sarmad Khoosat who directed and starred in the recent Pakistani film. “When I was at high school he wasn’t part of our syllabus,” recalls Hanif. “The people who read his books were considered rebels, edgy people who didn’t conform. Reading Manto gave me the idea that you can write about stuff that is happening right now. Somehow we believed that something that happened in the past is the subject of fiction whereas what is happening now is the subject of news or commentary.”

In the early 50s Manto wrote a number of essays entitled “Letters to Uncle Sam” which are distressingly prophetic on the direction that Pakistan was to take. In one, written in 1954, he wrote that the US “will definitely make a military aid pact with Pakistan because you are really worried about the integrity of this largest Islamic sultanate of the world and why not, as our mullahs are the best antidote to Russia’s communism. If the military aid starts flowing, you should begin by arming the mullahs.” In another essay, “By the Grace of Allah”, he predicted a future where everything – music and art, literature and poetry – would be censored. “He anticipated where Pakistan would go, but I think he would be quite horrified with some of the trends that have occurred,” writes Jalal. “He would have been a blistering critic of all that has happened in Pakistan in the past 35 years.”

The irony is that even though Manto foresaw the Pakistan that exists today it would now be harder for a writer like him to work than it was 70 years ago. “Times are tougher than they were in his time and we are now more intolerant as a nation,” says his daughter Nusrat. In the last year progressives, bookshop owners and journalists have been murdered by religious extremists. “I have lost count of how many journalists in Pakistan have been targeted – killing journalists is quite a popular sport,” says Hanif. “In 2016 could someone write as challenging material and get away with it?” says Suniya Qureishi, a relative of Manto who works for the British Pakistan Foundation. “Every time you see someone raise their head above the parapet challenging the ills of society they are taken out.”

In the absence of a new Manto the old one is finding new respect and a new audience. “His writing has aged phenomenally well,” says Hanif. “I read him 40 years ago and I meet kids who are reading Manto for the first time – you can actually see the light in their eyes. You can see their jaws dropping and they say, ‘What is this? Who is this guy?’” It is a question that deserves to be asked beyond India and Pakistan. “Manto is as skilled as the best short story writers of the Russian and western tradition” says Tanuja ‘and it is very sad that he has been erased from the literary canon.”

“You would not believe, uncle, that despite being the author of 20, 22 books, I do not own a house to live,” Manto wrote in one of his Letters to Uncle Sam. “If I earn 20, 25 rupees based on the rate of seven rupees per column, I take the tonga [horse driven carriage] and go buy locally distilled whiskey.” He would go to his newspaper offices, write a short story while there and buy alcohol with the payment received and towards the end of his life an addiction to alcohol, together with financial hardship, took a toll. He died in January 1955. Six months earlier he had composed his own epitaph which, although it was never used on his tombstone, suggests that the writer knew that his work would outlast him. “Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto and with him lie buried all the secrets and mysteries of the art of story writing. Under mounds of earth he lies, still wondering who among the two is the greater story writer – God or he.”

• Sarfraz Manzoor presents Manto: Uncovering Pakistan on BBC Radio 4 at 11.30am on 16 June.

Comments

Post a Comment